Calling All Solar Cookers: Interview with Dr. Robert Metcalf

Transcription by Barbara Kerr

Tom Sponheim: Welcome to the December 1, 2002 broadcast of Calling All Solar Cookers. We are speaking today with Dr. Bob Metcalf. He is a microbiologist at California Sate University Sacramento. Dr. Metcalf is one of the original founders of Solar Cookers International. He has traveled extensively on projects for SCI working cooperatively with the UN-AID, Plan International, and World Vision, as well as other international organizations. His specialty lately has been solar water pasteurization. Welcome, Bob.

Robert Metcalf: I am pleased to be with you this morning.

TS: Why don’t you fill in some of the gaps in what I mentioned, so people will know more about you.

RM: I was born and raised in Chicago and I did my undergraduate work in biology at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. And then I got my PhD in bacteriology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Since 1970 I have been on the faculty of biological sciences at California State University, Sacramento.

TS: Are you an active solar cooker yourself?

RM: I sure am and I have been since 1978 when I bought a solar box cooker from Barbara Kerr and Sherry Cole. I read about it in a small article and thought it would be interesting to try. I got one in June of 1978 and started cooking with it and have cooked at least 4000 meals with the sun. Here in Sacramento, usually about 200 days a year we can do solar cooking, and also in 17 other countries around the world using the sunshine to do some serious cooking.

TS: I must say, Bob, that when I first found out about solar cooking in 1987, you were the person I looked up in the phone book and called on the phone and asked if I could do anything. And you said immediately right away, “Yes, you can.” And had some suggestions for me. And that was the beginning of my solar cooking and work on promoting solar cooking.

RM: One of the wonderful things about solar cooking is that anybody who happens to come across the solar cookers one way or another, if they are interested in them, pretty soon they can get pretty expert about using solar cookers. And there are lots of things to do. What really is amazing about solar cookers is that so much of the effort that has brought the science to a very high level, has been done by volunteers… people like you and me…that find out that this is something the world needs to know about and then use our special skills to help promote this. It is also very energizing. This is my 24th year doing solar cooker things and it is just….you don’t get burned out…you just get energized doing solar cooking.

TS: So what I wanted to talk about today was a little bit about food pasteurization or making food safe to eat or how food might actually become unsafe to eat if it was held at the wrong temperature for too long a time. Then talk about water pasteurization and the difference between sterilization of water and pasteurization of water. And then some of the science behind how we know that pasteurization of water actually makes it safe to drink. How that is done. And then I would like to talk about some of the trips you have taken to different countries and what you have seen recently in those countries on those trips. So why don’t we start with food pasteurization? Actually let’s start with food spoilage…

RM: Food safety.

TS: Yeah. Safety. Give us a basic background with food safety and solar cooking.

RM: With cooking foods mainly one is concerned with cooking meats that they might become contaminated with organisms that could cause disease, mainly bacteria. And if you cook the meat to 65º C or that’s about 160º F you are going to make the meat safe to eat. I have never had a problem of putting cold meats out into the solar cooker and facing it to the mid-afternoon sun and letting it sit there for a few hours. It is not going to get warm. Bacteria really start growing at temperatures that are about, starting about 20º C up to 40º C. That is usually the range. Or maybe 15º C to maybe 45º C.

TS: What would that be in Fahrenheit?

RM: O.K. So you are talking about 70º Fahrenheit and going up to about 110º Fahrenheit.

TS: So that would be the danger zone?

RM: Yes. That is where bacteria can actually grow. Bacteria can survive up to about 130º or 140º F. Most of them are going to stop growing. There is one bacterium that can actually grow at 120º F but that organism forms a spore and the bacteria that don’t form spores, they are all killed when foods are cooked to 160º F.

TS: So let me get this straight. You mentioned this to me once before … about spores. So is it basically that the bacteria senses that the temperature is getting to be in the range where it is not going to be able to survive, so it basically “lays an egg” that can survive that temperature even though the original bacteria is going to die?

RM: No. The bacteria that get into foods, they are usually going to be either just vegetative cells themselves or else they could be endospores of the bacteria. When the foods are starting to cook, they do not have enough time to get into spore formation.

TS: I see. So the food may contain spores and just regular cells. And the spores end up surviving.

RM: Yes. The spores survive in the foods and cooked foods then have killed off bacteria like salmonella, and shigella, and Staphylococcus aureus, that cause various types of diseases with uncooked food , or under cooked food, or food that gets contaminated afterwards. But it is spore formers then, and one is the bacterium that causes botulism, and another is the bacterium that causes …. Clostridium perfringens is the name of it…and it causes another type of food poisoning. And those spores can survive the cooking temperatures…cooking temperatures which kill off other bacteria. And then when the food temperature is lowered to below 120° F (50° C) the spores could then germinate and grow into vegetative cells which then actually produce the toxins which would get one sick.

TS: Now is there … let’s say there was a period of time…three or four hours after the food was cooked in the solar cooker where it might be just sitting there. Is there enough time during that time for the spores to actually hatch and produce enough of a colony that they would actually hurt you?

RM: Yes. You want to keep the temperature either above 120° F or below 50° F. You would like to keep the food in that window there for less than two hours.

TS: O.K. I have a question that I have heard people say: :What if you had a piece of meat that was basically spoiled, why can’t you just cook it and kill everything in it and then eat it?”

RM: Well, you could. But it wouldn’t taste very good. So it would be safe microbiologically but it still would not taste very good.

TS: Could there be toxins from the …

RM: Usually not with meats. Meats are going to have usually gram negative bacteria that will more likely contaminate. That would be the ones that would grow beyond that and one would have to eat those bacteria alive so that they could then cause infections in people.

TS: I see. This might be a good time to talk about the canning of fruits – and whether or not you can can vegetables in a solar cooker.

RM: O.K. Again the major problem are these spore forming bacteria and particularly the spores of clostridium botulinum,, which can cause botulism. And those spores can survive boiling temperatures…the temperatures you get over a stove or you get in a solar cooker. After foods have been cooked, where the spores might be able to grow, such as in vegetables, that if the spores have survived that when the food is then cooled down below 110° F as with Clostridium botulinum that the spores can germinate and grow and then produce toxins that could get one sick when one eats the food.

TS: So, what is the guideline then for canning in a solar box cooker?

RM: O.K. The guideline for canning is that you only are going to can foods which are acidic, that the measure of acidity is listed in the pH values. You want foods that have a pH of 4.5 or below and that would be…I have canned cherries, and peaches and applesauce. You have got tomatoes, usually they are acidic. You want to add a little squirt of lemon juice to it also to lower the pH.

TS: And the acidity, then, stops botulism from growing?

RM: Yes. But even if you have spores of Clostridium botulinum, that are in something like peaches that have a pH of around 3.5, it is too low of a pH, too much acidity, for the spores to germinate and grow. And that is true in the canning industry world wide … that foods that have a pH of 4.6 and above have to be given a very severe heat treatment to make sure that all the spores of Clostridium botulinum are killed. Those are going to be heated in a pressure canner so that the temperature gets above 100° C., above boiling. It gets up to 250° F from 212° F, which is boiling. And at those temperatures then within a relatively short amounts of time, the spores will be killed.

TS: So for basically solar cooking, you should try to keep food, especially if you have meat, outside of that danger range. It should not be in that range for more than two hours. So I imagine that when the food is sitting in the cooker at the beginning of the day it is still cold from being in the refrigerator and then …

RM: Yes. And as long as then it eventually gets cooked. You heat the food up to 160° F, you are going to kill off all except the spore forming bacteria. Those would be the organisms that could cause the most trouble.

TS: And then, as long as long as you don’t let the food keep sitting in the danger zone for too long afterwards, you should be safe.

RM: Right. And that is particularly for spores then that will survive the initial cooking to grow and to get to large enough numbers that they could cause food poisoning. That won’t happen in just an hour, but two hours is usually the guideline.

TS: O.K. We have been talking about meat. How about other foods?

RM: Well, other foods, something like beans, again, no problem. You have got to really cook those things and so even if the water is contaminated that one is using to make beans or rice, the bacteria that cause disease in water are not going to survive the cooking. So the rice will be cooked and so will the bacteria that might cause disease. And again it would be the survival of spores in cooking foods that then after the foods are cooked, if there is still left over food and the food can’t be refrigerated, it might give an opportunity for bacteria to start growing in that food and then give some food poisoning problems.

TS: So why is it that meat seems to be the one … we usually think of food spoilage happening in meat but not so much to other foods.

RM: Because the organisms, the bacteria that do cause disease are found on animals like chickens, and turkeys, and cattle and pork. Therefore in the preparing of those meats, you get the bacteria that also can cause food poisoning with those.

TS: O.K. So I think we have a good idea about food safety. And we have some documents up on the Solar Cooking Archive that you have written and an interview I did with you a few years ago about this. People can read more.

Let’s talk about water pasteurization and water sterilization. The general thought out there is that water has to be boiled for 20 minutes to make it safe to drink. And I know that Solar Cookers International has been spreading the word that that is not necessarily necessary. Give us the low down on that.

RM: O.K. Anybody who is a microbiologist knows that milk does not have to be boiled to make it safe. Milk pasteurization temperatures are about 71° C. that is about 160° F. for just 15 seconds. And the organisms which cause disease in milk or water are not those that produce these heat resistant endospores. The spore forming bacteria are not ones that you are going to get disease by drinking. If you have cuts and the spores get into the cuts, you can get gangrene from some of those spores. But you are not going to get diseases from spore forming bacteria by drinking them.

TS: Oh, I see.

RM: And so they can survive, and they will be in milk. Spore formers will be in milk and no problem because they don’t cause disease in your intestinal tract.

TS: So, if a spore is floating around in water, it is not necessarily going to have the nutrition it needs to actually start multiplying. So the worst that can happen is that you will drink that spore into your body and at that point it can't actually hurt you.

RM: Right. And you also have a lot of normal bacteria that grow in the large intestines. It is a very competitive situation. And the bacteria that form spores do not compete well in that environment. So you don’t worry about clostridium botulinum spores, if you happen to swallow a cluster of botulinum spores. You only worry about that if it can grow in a food and then produce a toxin that then would get you sick eating that - the toxin.

TS: O.K. I see. Now which bacteria are actually killed at the temperatures you are about … water pasteurization temperatures.

RM: O.K. There are three levels of temperatures which will kill microorganisms rapidly. By rapidly, I mean that at least 90% of the microbes will be killed within a minute at this temperature. O.K.? So, if you have 5 minutes at this temperature you would get 99.999% killing of microorganisms. And at 131° F, which is 55° C., killed rapidly at these temperatures would be the cysts of protozoa, that would be Guardia, cryptosporidium, and entamoeba. Also the eggs of worms are killed rapidly at that temperature. At 140° F, which is 60° C., you have the major causes of infectious disease being killed. These are bacteria; the cholera bacterium, shigella, salmonella bacteria and those that cause typhoid, certain strains of Escherichia coli, the enterotoxogenic strains of E. Coli, and also the virus called the rotavirus which is a major cause of disease in children. And at 140° F (60° C), within a minute you will get 90% killing of those. So if you have water at that temperature for five minutes you are going to have a five-log reduction. You would have to have 100,000 bacteria in that to have one surviving. And then with another minute …, six minutes then, you would have to have 6 million to have one survive that temperature. Usually you don’t get that high counted in bacteria. And then the one water-borne pathogen that has a slightly more resistant temperature to inactivate, is the Hepatitis A virus which is not much of a problem in developing countries, because children get Hepatitis A when they are young and it is a mild disease. Hepatitis A is severe if you get it as an adult, however. And at 149° F, 65° C., you get 90% killing of Hepatitis A virus every minute. At 140° F, it takes two minutes to get a 90% inactivation.

And so based on that type of knowledge, and looking up in the literature the temperatures at which these waterborne pathogens were killed and then running experiments starting in the 1980s with a graduate student, David Ciochetti, and taking water from our American River, and also then adding the bacteria, various bacteria, to the water, as we heated water kind of relatively slowly in a solar cooker (and at that time it was a box cooker), by the time we get up to 140° F., we can’t recover any more microbes even though we might have had a million per milliliter to start with, which is an exceptionally high number. We also, then kind of wanted to put in a bit of a safety factor, and so when we published our work in 1984 we suggested that water that is heated in solar cookers … if it is heated to 149° F (65° C), … that would be sufficient to totally inactive all the cysts, the protozoan cysts, the bacteria, the rotaviruses and even the Hepatitis A virus. That is just getting it up to that temperature.

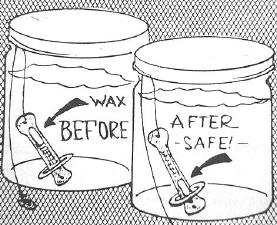

When I have done a lot of microbiological tests, particularly in the last two summers in Tanzania, I found that the lethal temperatures for bacteria really start working at about 55° C., that is 131° F, and from 55° up to 60° C., bacteria are getting killed off. By the time I have gotten naturally contaminated water to 60° C, I can’t recover any more bacteria in there that don’t form spores. That is just getting it up to 60° C., so if you were to draw a graph of the temperature of waters and on the left side the temperature and underneath, on the right side, you have the times, when you are above 55° C., that is the time you are in the lethal condition for the organisms which cause disease. Initially, I thought 65° C., was a safe temperature. I now, this last summer, when water was getting up to just 60° C. and then I let it cool down…I was drinking that water that initially was heavily contaminated. I was confident enough that the microbes that cause disease had been completely inactivated in that water. So I would really like to … Solar Cookers International then developed this water pasteurization indicator, which is a clear plastic tube which has a wax in it. The wax fills up about a quarter of the tube and you put that into a container of water. If the water heats enough to melt that wax, you know that the water has reached pasteurization temperatures.

TS: I know that bees wax melts at about 62° C. Would you think that would be a safe indicator at this point.

RM: It would. I have tried beeswax. I don’t have my data right here but sometimes I have found it variable … the temperatures. And, if anything, I think on the safe side, it melts higher than that. Waxes have stated temperatures at which they melt at, but they actually start changing phase in a range of temperatures. I am really looking for a good wax that melts at around 62° to 63° C. That would be really good … about 145° F. That would be one that…

TS: So you don’t think that, at this point, bees wax is safe enough to rely on?

RM: I have run those tests with beeswax and I don’t have the data with me…

TS: Maybe we can talk about that at another time. Because it would be nice if there were some wax that occurred everywhere in the world that could easily be gotten to by people and they could make their own thermometers.

RM: That is correct. And when I have actually run those experiments, I have put beeswax into WAPIs, made the water pasteurization indicators and put those in there. As I recall, the temperature is much higher than 62° C that it melts at.

TS: I see.

RM: And so, when waxes are given temperatures (in the literature) you really have to try it out and see if it is going to be melting at that temperature. But I agree that that is something that needs some further work … the beeswax.

TS: O.K. So now we understand a bit about how water pasteurization works. And is it true that maybe it is recommended that people boil their water, because the actual boiling of the water acts as a temperature indicator?

RM: That is from when David Ciochetti and I

published our paper back in 1984, we speculated that the reason that

organizations, such as the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease

Control in Atlanta, if the water is unsafe, they tell the people to boil the

water because microbiologically it needs to get boiled, but nobody has any idea

what the temperature is from the time you put it on until you get to a boil.

Then you know it is at 212° F, at least at normal altitudes. And what the

world really needed to develop, the World Health Organization, is to develop a

reusable water pasteurization indicator and they never did that. Solar Cookers International is the one

that recognized that it would be useful. I knew that was what I wanted and I helped … I got some help from Fred

Barrett, who was with the US Department of Agriculture in the late 1980s and he

came up with the idea of a wax in it. And then a graduate student in mechanical engineering at UC Berkley, Dale

Andrietta, he came up with the

model that we then have been using since that time … This WAPI where we have a

stainless steel washer that holds it at the bottom of the container, because in

solar heating, the bottom is coolest last, unlike over a stove, it is going to

be the slowest to heat. And so we

developed that and it is really a remarkable device. Every body that works for

the Peace Corp and works for … goes any place in developing countries and is

boiling their water now, if they got a WAPI from Solar Cookers

International. And that wax melts

at about 70° ., about 160°

, which is much … very safe to drink

that water. That has been safe for

a long time. And if people would just use that WAPI when they are using gas or

they are using other types of fuel to heat their water, and then turn the water

off when that wax melts, they could probably save 50% of their energy for

heating the water. The water also

would not taste as bad as it does when it boils. And you also wouldn’t make the water as

dangerous as when it is boiling. It is still going to burn you at 70°

C. One second, if you stick your

hand in that “WOW” you have got a

burn. But at least it is not going

to be 100° C. that then could spill and cause serious

problems.

RM: That is from when David Ciochetti and I

published our paper back in 1984, we speculated that the reason that

organizations, such as the World Health Organization or the Centers for Disease

Control in Atlanta, if the water is unsafe, they tell the people to boil the

water because microbiologically it needs to get boiled, but nobody has any idea

what the temperature is from the time you put it on until you get to a boil.

Then you know it is at 212° F, at least at normal altitudes. And what the

world really needed to develop, the World Health Organization, is to develop a

reusable water pasteurization indicator and they never did that. Solar Cookers International is the one

that recognized that it would be useful. I knew that was what I wanted and I helped … I got some help from Fred

Barrett, who was with the US Department of Agriculture in the late 1980s and he

came up with the idea of a wax in it. And then a graduate student in mechanical engineering at UC Berkley, Dale

Andrietta, he came up with the

model that we then have been using since that time … This WAPI where we have a

stainless steel washer that holds it at the bottom of the container, because in

solar heating, the bottom is coolest last, unlike over a stove, it is going to

be the slowest to heat. And so we

developed that and it is really a remarkable device. Every body that works for

the Peace Corp and works for … goes any place in developing countries and is

boiling their water now, if they got a WAPI from Solar Cookers

International. And that wax melts

at about 70° ., about 160°

, which is much … very safe to drink

that water. That has been safe for

a long time. And if people would just use that WAPI when they are using gas or

they are using other types of fuel to heat their water, and then turn the water

off when that wax melts, they could probably save 50% of their energy for

heating the water. The water also

would not taste as bad as it does when it boils. And you also wouldn’t make the water as

dangerous as when it is boiling. It is still going to burn you at 70°

C. One second, if you stick your

hand in that “WOW” you have got a

burn. But at least it is not going

to be 100° C. that then could spill and cause serious

problems.

So Solar Cookers International, without any grants, without any outside funding but having volunteers help out, we have come up with the water pasteurization indicator. It is really a spectacular device.

TS: It is very clever and we have pictures of that up on our web site. So, let’s talk a little about water quality on the ground in the countries where you have been. Give us an idea of what you see when you go there; what happens when you test the water; and how do you go about testing the water out in the field?

RM: That is where my background as a microbiologist has been very useful. From the very first International Solar Cooker project I had with solar box cookers in Bolivia, back in 1987, I was up in the altiplano of Bolivia where they get water from Lake Titicaca and suspected that the water was unsafe to drink but had no way of testing it, because the traditional methods for testing water require a laboratory, and require incubators, particular an incubator around 44° C. and so essentially water is not tested most places around the world to see if the water is safe or not. You don’t know if a pump is safe or if it has been contaminated because the traditional procedures the World Health Organization recommends, which are very useful in developed countries like ours, but they are impractical to use in developing countries. So I was looking for methods to test water without having a laboratory.

In 1988 then, there was a new approach to water testing. The Colilert procedure was developed by what is now the Idexx Company in Westbrook, Maine. It was based on an enzyme produced by Escherichia coli. Escherichia coli, or E. coli, is the indicator of fecal pollution in water. That is because E. Coli is found in human feces whether you are healthy or sick. You have about 100 million to a billion E. Coli bacteria per gram of feces. So is always in feces. It doesn’t grow in water outside the body. It dies off slowly, similar to other bacteria which cause water borne diseases, such as cholera and typhoid fever. It is also relatively easy to detect and this enzyme that E. Coli produces is detected in these particular tests… the Colilert tests. One that you have a picture of me on the web site then that is the tube that is yellow there. That is the Colilert test. Ten milliliters of water is added to that tube. Then because it is an enzyme test, you incubate the tubes where E. Coli loves to grow and that is body temperature. And you have a body, so put it on your body and incubate it … and sleep on it at night. You want to do that so that the bacteria in the Colilert material there, the suspension that we have, can grow from one cell up to millions of cells. It can do that in about 10 to l4 hours or so, if you keep it at body temperature. And so if E. Coli is present and you incubate it at body temperature, within about 14 hours, the tube will change color. It will eventually turn yellow; but also if we shine an ultra violet light on it, a battery-operated ultra violet light, it will fluoresce blue. That indicates that E. Coli is present and that you have bacteria from feces in the water, and you might have organisms that cause cholera or typhoid, or rotaviruses, or other type of infectious disease in the water.

TS: So you take with you this Colilert test kit, which is basically a number of test tubes that have some sort of powder in them

RM: The nutrients are in there, basically just a powder in there that they can grow on.

TS: And then you open up the tube and you put a small sample of water in there and you close it up. Then you keep it next to your body for 10 to 14 hours.

RM: That is right. And then if it fluoresces when you shine a blue light on it, a UV light on it, then you know it has E. Coli in it and it is unsafe to drink.

TS: I see. I notice they turn yellow when they are seen in regular visible light. It that helpful for people to see that the water may actually be contaminated…the fact that it is yellow?

RM: That is another substrate in there. Another food source in that medium is one which E. Coli can use, but then other bacteria, called coliform bacteria, can also use that. And in the United Stales our water standards are “No coliform bacteria in the water.” So in the United States that never should turn yellow. Coliform bacteria, however, they are also found out in the environment. And they can grow in the environment. They are found on plant materials and they don’t indicate a public health hazard. So if the tube turns yellow, but it does not fluoresce, you’ve got coliform bacteria but not E. Coli, among that coliform, so it is probably an environmental contaminant. When I have done these tests in Tanzania, the last couple of years, when I get water from pumps that seem to be well protected, I will get coliforms, but not E. Coli. Some good water sources, and there are not very many, but good water sources also have coliforms but not E. Coli. In rain water, you can get coliforms but not E. Coli. So you really want to see if it fluoresces then.

Now, when you heat the water in a solar cooker, and you take the water before it is heated and it will turn yellow and fluoresce blue, and then after you heat it, all the coliforms are killed off, so the thing will be clear. So that is a dramatic demonstration then even without using the UV light … that it goes from yellow to clear.

TS: I see. Do people in various places you have been, do they believe that the water could be contaminated if it is something they can’t see, if the water looks clear?

RM: Well, there is the second thing that we also use, which was also shown in that picture of me, there is a thing, it is called a Petrifilm and it is made by the 3M Company. And it is used for food products. It is a little piece of cardboard and it has a circle of nutrients for bacteria that are about, they are actually about 2 ½ inches in diameter, about 5 centimeters or so in diameter. And you lift up a little plastic film above this and you add 1 milliliter of water. That is all you add. You put the film down on top of it and then you squash that 1 mil over the surface of the nutrient so the bacteria are then distributed over that very thin film of nutrients. And within the Petri film, there is another substrate that E. Coli can use that goes after the same enzyme. This time you do not need a UV light but if a colony grows and it turns blue, and again you incubate it on your body. It is a little more awkward. I put it between pieces of cardboard and put it underneath my passport and my money belt and then I sleep on it at night. And in about 10 hours one cell in that medium of E. Coli has grown up to millions of cells and you can start to see a blue colony. And then a couple of hours later you can see gas bubbles being produced around that colony and that indicates that E. Coli is present in the water.

I have used these two tests together: the Colilert and the Petrifilm. And at the workshops that I have had in the last two years in Tanzania and also this last summer in Nairobi, Kenya, I go over the bacteria size, I go over how they grow, what these tests are all about. We have people sample the water before we heat it that has been, in Tanzania, that is naturally contaminated. Or in a workshop I have had in Nairobi or Dar es Salaam, I will artificially contaminate it. Then we heat that water and we test it afterwards. And I think that people can understand. The way that these tests present themselves, you have to let it grow to get up to millions. That there are bacteria there but they have to get up to millions before you can see a colony because they are so tiny. But then you can see the colonies developing and then you can see the before you heat the water and then after you heat the water. That is a very dramatic, educational presentation of water supplies … whether the water is safe or not. And I have this year, I am working right now with health workers in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, the biggest city in Tanzania. And they were at my workshop a year ago and they really wanted to use some water tests for the Dar es Salaam for water supply. And this year then I have provided them with Colilert tubes and Petrifilms enabling them to test water in their distribution system. And in Dar es Salaam and some of these other big cities in developing countries, there are illegal connections to the water sources, sometimes the water pressure is not high and you get contamination. And the people in Dar es Salaam can’t test anything because the standard procedures are too costly and they just can’t do it. So here providing them with these testing materials that cost about $1.30 a piece which I am paying for for them to use, they can go and test water sites. They have been able to test, particularly where shallow wells are found that they have found contamination, E. Coli contamination. And they have been able then to post “You need to boil this water because people have gotten cholera in this area and the water is unsafe to drink.” So they can assess water quality and then they can make some recommendations. We don’t, we have not gotten these people WAPIs yet. That is just the water testing component but I have had workshops in Tanzania and then this past year with a woman that helped me, Christine Polenelli, from the Department of Health in Australia. She helped me this last year, she is a former student at CSUS and has a very good microbiology background. We held workshops in the cities as well as in the villages and when you take village watering sources and you have people setting up Colilert tests and Petrifilm tests, incubating them on their body overnight and then the next day they see “My gosh! There are blue colonies in those in the Petrifilms and then the tube will fluoresce. It is yellow and it will fluoresce with the UV light and then after it is heated everything looks good…That is very powerful. It is a very powerful teaching method for people to assess if their water is safe or not and then to enable these people to do something with it. I think the Colilert and the Petrifilm are going to revolutionize the ability to assess water in developing countries. And

TS: It looks like we have to revolutionize the ideas that people have about how that needs to be done, though, for that to happen.

RM: Yes. And that is why a lot of the work in microbiology of testing local water supplies, heating water, pulling out samples at 55° C (60° C) and doing a lot of microbiology, I can do that now with these tests. This is something, again, the science is getting very well established about that. And my partnerships in Dar es Salaam, and I plan on partnerships this next year in Kenya with the area in Western Kenya that Solar Cookers International is going to be focusing on for a solar cooker project. I also plan to go there next summer and introduce the water testing, water pasteurization. We are going to be collecting data which then I am very confident are going to show people around the world that there is something relatively simple and inexpensive that can assess water supplies in developing countries and easily people can learn how to use these and again, a transforming step. Just like cooking with the sun in solar cookers is a transforming step away from fire.

TS: You were recently in Kenya dealing with the Solar Cookers International center there. Can you give us an idea of what you were up to when you were there?

RM: Solar Cookers International has an East African regional office in Nairobi. We have had that for about 5 years. Margaret Owino is the coordinator of that office and now there are two other staff people that are in that office. This last summer, Christine Polinelli and I, after we were in Tanzania, we went to Nairobi and we worked with the East Africa regional office and had a presentation about solar cookers and solar water pasteurization on one day for about 60 people from 17 organizations and then Christine and I ran a two day workshop on water testing and water pasteurization for again about 60 people, going through the procedures of how microbes cause disease in water. What we look for the indicators. How they can be detected. How these tests work. And then water pasteurization. And again it was a very exciting experience. We had people in that country that work on water testing and use some of these traditional methods that were very excited about the ease and the accuracy of using these … the Colilert and the Petri film. And then after the workshop, the 17 groups each got some Colilert tubes and some Petrifilms to use for water supplies to get some assessment and to get some feed-back to the SCI office there in Nairobi about recommendation about things that they like. When one test might be superior to another. Any problems they have had. Possibilities and recommendations. So it is another small partnership that we have with people who really need to test water in areas and enabling them to do them with these projects. In working with the SCI’s East Africa office, just wonderful people. Really exciting to be able to contribute the water testing-water pasteurization and this next year then as SCI’s East Africa office focuses on an area in Western Kenya to try to establish over a three year period a sustainable solar cooker project. That’s going to be very exciting. It is called Sunny Solutions. We hope to demonstrate that people will be willing to buy solar cookers and you are not going to have to subsidize these in an area that is fuelwood short, sun rich, and has water supplies that are unsafe. There are a lot of water borne diseases there.

TS: That sounds exciting. We will have to talk with you about that another time. Well, I want to thank you for all this information. This is probably the most jam-packed interview on solar water pasteurization that any body is going to find on the WEB. Is there anything else you would like to mention that I have not asked you about, before we close?

RM: Let’s see. I think that just encouraging anyone who is out there and has an interest in helping people who desperately need to know that there is an alternative to fire, to start doing something with solar cookers and check in through the web site that we have here for solar cookers. And also, help support Solar Cookers International, this volunteer organization that really celebrates the successes people have around the world with different cookers showing people that there is an alternative to fire…The one organization in the world that really is trying to teach people that with sunshine, you have got an alternative to fire, you can use it for cooking with the world’s simplest solar cooker, the CooKit, that SCI has or with the box cooker like I started with, or the SK 14s. There are lots of opportunities to do some solar cooking and 2 ½ billion people in the world desperately need to know about this. And in Tanzania, over 90% of the energy is from traditional fuels. 32 million people each day are using about 50 million pounds of wood and that is all ashes at the end of the day. That is not sustainable. And those of use who know about solar cookers and experience things, there are a lot of things that individuals can do, even if they have other full time jobs as you and I have. They can really contribute so that in 5 or 10 years it becomes well known around the world. The science is solid. Now, what we need to do is to spread this science.

TS: Yep! And that is what we are busy doing. So, thank you so much, Bob. We will check back with you in 6 months or a year and see if we can get an update on what you have been up to.

RM: Thank you so much for having me on and for all the things that you do to disseminate information around the world about solar cookers.

TS: Thanks, Bob. See you. Bye!

RM: Bye!